During my rotation, the most exciting change in the laboratory was getting a new tissue processor. For those who don't know much about anatomic pathology, making an accurate diagnosis for patients relies extensively on a technique that hasn't changed much since the 19th century: hematoxylin and eosin stained histologic sections of human tissue specimens. These are cut from fixed and processed tissue embedded in paraffin wax by histotechnologists. The processing part requires a lengthy procedure, often done overnight. It includes fixation of fresh tissue in formaldehyde solution (formalin), dehydration of the tissue with alcohols, clearing with xylene, and embedding the tissue in paraffin wax in a "block." While the processing used to be done by hand long ago, there are many steps using solutions and solvents required in a modern tissue processing program, and clinical workflows tend to have a large number of specimens, so an automated machine is the norm. Here is a decent source (from a big company...) that explains it for those who may not have much exposure:

https://www.leicabiosystems.com/pathologyleaders/an-introduction-to-specimen-processing/

|

| The old processor is on the right |

|

| Getting the the new one in the door. |

|

| Plug it in! This model - the STP 120, can cost ~$25,000 if purchased new at full price per my online research, and it seems to be a cheaper alternative. |

|

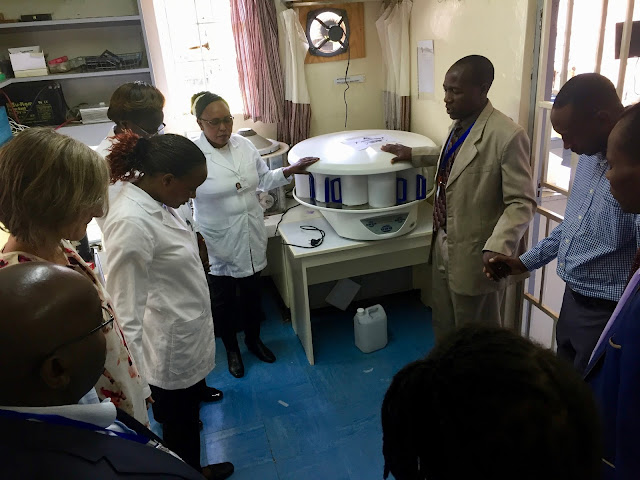

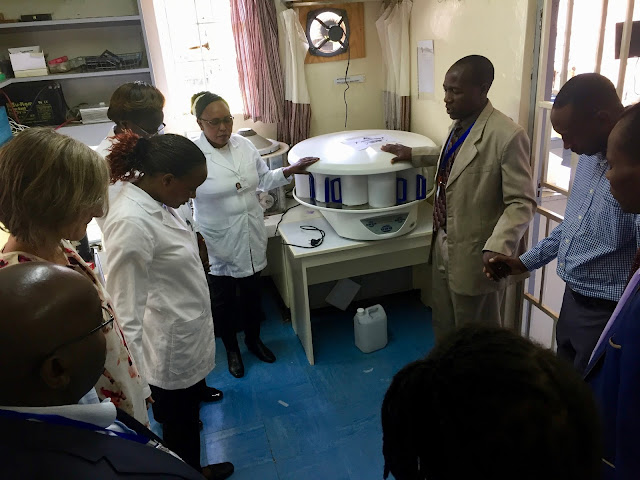

| Dedication and prayer for the processor with hospital officials! This usually does not happen at UWMC. |

|

| Lifting up the hood and showing the rotating baskets and solution containers or retorts. |

Something you might have noticed with this processor (and the old one), if you've been around them before, is it looks a bit different. Here's more what you might expect (from the Leicabiosystems site):

You are probably used to seeing an enclosed tissue processor such as this one. All of the tissue is in one container (or retort) and the solutions are heated as needed and pumped into and out of the retort. In the "dip and dunk" processors that we use in the Kijabe lab, the specimens are moved from solution to solution in a rotating carousel fashion. These models don't have as many features for increased temperatures and pressures to reduce processing times and increase efficiency as the enclosed processors do, but they are less expensive and easier to maintain, making them a good choice for Kijabe's pathology lab where turnaround time is less valued and cost, reliability, and maintenance issues are more important. I had never seen the dip and dunk design before, and I'm glad I got to help install and dedicate this shiny new piece of equipment!

|

| Hooray for the new processor! Best wishes, and may it serve the Kijabe lab well for many years. |

You are probably used to seeing an enclosed tissue processor such as this one. All of the tissue is in one container (or retort) and the solutions are heated as needed and pumped into and out of the retort. In the "dip and dunk" processors that we use in the Kijabe lab, the specimens are moved from solution to solution in a rotating carousel fashion. These models don't have as many features for increased temperatures and pressures to reduce processing times and increase efficiency as the enclosed processors do, but they are less expensive and easier to maintain, making them a good choice for Kijabe's pathology lab where turnaround time is less valued and cost, reliability, and maintenance issues are more important. I had never seen the dip and dunk design before, and I'm glad I got to help install and dedicate this shiny new piece of equipment!

You are probably used to seeing an enclosed tissue processor such as this one. All of the tissue is in one container (or retort) and the solutions are heated as needed and pumped into and out of the retort. In the "dip and dunk" processors that we use in the Kijabe lab, the specimens are moved from solution to solution in a rotating carousel fashion. These models don't have as many features for increased temperatures and pressures to reduce processing times and increase efficiency as the enclosed processors do, but they are less expensive and easier to maintain, making them a good choice for Kijabe's pathology lab where turnaround time is less valued and cost, reliability, and maintenance issues are more important. I had never seen the dip and dunk design before, and I'm glad I got to help install and dedicate this shiny new piece of equipment!

Whoa!What a victory for the lab! Very cool you got to help install it.

ReplyDelete