11 January 2015

Our

average work day consists of signing out the cases grossed the previous day -

about 20-25 surgical cases (including biopsies), 3-5 cytology cases, and 2-4

peripheral blood smears. There are a couple bone marrow cases and 10-20 pap tests per week. Since

the provided histories are often limited and there is no electronic medical

records, we sometimes go find the patient on the wards and gather information

from the clinicians and chart. Some of the more sophisticated tools available

to us include reliable internet, Olympus microscopes with attached cameras, a

library more complete than that at the Seattle VA Medical Center, Dragon

dictation software and headsets for grossing, a computerized reporting system

(FileMaker), and collegial surgeons who visit us often to discuss their

patients. However, without a doubt, the resource that helps me the most in my

daily tasks, is Ginger Jensen. Ginger diligently and efficiently assists me in

the gross room – triaging cases, labelling blocks, changing blades, cleaning up

messes, pointing out mistakes, confirming patient identifiers, and offering

keen advice about when to consult Rochelle. She is patient and excellent

company.

I am impressed that the hospital

has fairly reliable electricity thanks to a backup generator. Histology labs

are dependent on a significant amount of infrastructure and relatively

complicated equipment. Electricity is required for the slide drying oven,

ventilation fan (to reduce formalin fumes), microscope lights, computers, and

freezing blocks of ice to cool the paraffin blocks prior to microtome

sectioning. Perhaps this is the reason there are so few anatomic pathology labs

in Sub-Saharan Africa. We are not aware of another lab in this region of Kenya,

other than in Nairobi. A critical mass of health care capacity must be reached

before a hospital can support and benefit from an anatomic pathology lab. There

must be surgeons operating consistently enough (and who have the required

operating room infrastructure) to provide enough specimens to justify the

expenditure for technician salaries, equipment purchase and maintenance,

reagents, and space.

The largest barrier to providing

crucial diagnoses to guide surgical treatment is the pathologists themselves.

When Kijabe goes without a volunteer visiting pathologist, they send the

specimens to Aga Khan University Hospital in Nairobi. Many of the specimens

sent there in mid-December have not yet had a diagnosis returned. Like many

medical sub-specialties, training of pathologists in Kenya is complicated by

lack of adequate residency training opportunities. To train the future

generation of Kenyan pathologists, there first has to be enough pathologists to

tend to the diagnostic needs of the country and then enough to have time to

dedicate to teaching. In my opinion, teaching and mentorship is one of the most

sustainable contributions foreign physicians of any specialty can make to a

resource-limited country. Yet, like any action by a well-intentioned

researcher, medical volunteer, missionary, or NGO-organization, even teaching

carries the risk of doing more harm than good. Who can blame a Kenyan physician

who is trained in pathology to seek employment in Dubai, England, or the U.S.

if the opportunity presents itself? The “brain-drain” of medical specialists

occurs because many receive training in Europe where professional and personal connections

develop, which provide routes to leave one’s home country for extended periods

or even permanently.

Here are some cases from the first week:

|

| #1 Left upper eyelid and nose, biopsy: Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (recurrent) invading skeletal muscle and adipose tissue. |

|

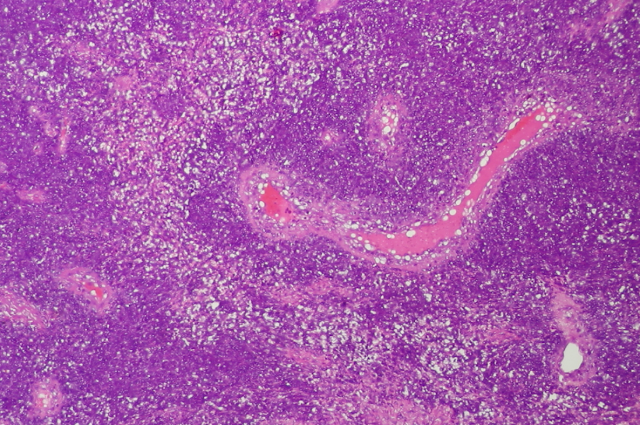

#2

Patient: 3 year old male status post hemimandibulectomy for

jaw mass.

Gross: A tan-white, firm mass (7.0 cm AP x 2.5 cm ML x 3.5 cm SI) has its

epicenter in the mandibular bone. The mandible is fractured posterior to two

molars. The bone is porous and thin.

Diagnosis: Low grade

spindle cell neoplasm, eroding bone and extending to apparent medial and

lateral margins; consistent with a desmoplastic fibroma. Consultation was provided by pediatric pathologists at Seattle Children's Hospital.

| | | |

|

| #2 High power view of jaw mass |

|

|

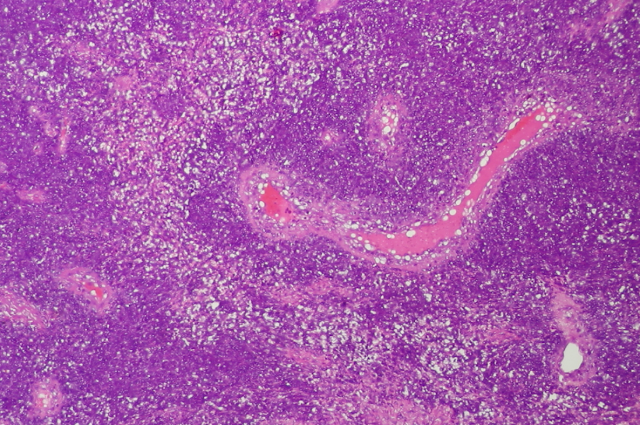

| #3 Patient: 30 year old HIV positive woman. Sharply delineated gluteal and sacral skin ulcer. Lesion spread from initial small vesicle. Photo of the lesion. |

|

|

| #3 Low power view at interface of normal skin and ulcer. |

|

#3 High power view

of ulcer.

Diagnosis: Skin,

sacral and gluteal, biopsy: ulcerated skin with neutrophilic inflammation and

epithelial cells with probable viral inclusions, consistent with herpes simplex

virus infection.

|

|

|

#4 Patient: 36 year old male with slow-growing left elbow

mass.

Diagnosis: Malignant small round blue cell neoplasm. Differential include Ewing sarcoma, neuroectodermal tumor, others. Consultation was provided by UWMC bone and soft tissue pathologists.

|

|

|

| #5 Peripheral blood smear from pediatric patient with microcytosis (MCV=76 fL) without anemia and numerous target cells. Diagnosis: Thalassemia trait. |

|

Other cases included two chronic myeloid leukemias on peripheral smears, and a multiple other neoplastic pediatric and bone and soft tissue cases.

|

| My desk on the right and Dr. Garcia's on the left. Excellent library of slightly outdated pathology text books. |

|

| Slide staining station. |

|

| Phyllis cutting at the microtome and Peris scooping tissue onto slides from the water bath. |

|

| Gross bench with computer access to the pathology database and wireless headset for direct dictating. |

|

| Main door to anatomic path lab. |

|

| Slide storage corner. |

Thanks for an excellent overview of a representative day in the life of a visiting pathologist. All is well in Montana. The skiing continues to be excellent and winter fishing is reasonably successful.

ReplyDelete